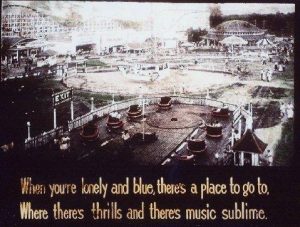

From the 1920s through the 1960s, summertime in Kansas City meant a thrilling trip to Fairyland Park.

The 80-acre amusement park in Kansas City, Mo., offered daring rides, an outdoor dance pavilion, a large swimming pool, and later, a drive-in movie theater.

As we move into the summer of 2014, we take a trip back to the heyday of a local summer ritual for many, but not all, Kansas City residents.

Every child’s dream

Maria Brancato Accurso grew up living a child’s fantasy. She and her family lived inside Fairyland Park.

At first, they would go after Memorial Day and return to their home in the Historic Northeast in mid-September.

Eventually, the house was winterized and she and her family would live there all year.

Accurso points out the house, in the same building as the park office, just inside the arched entrance to the park.

A family business

Accurso’s grandfather, Salvatore “Sam” Brancato, a Sicilian immigrant and blacksmith by trade, came to the United States in 1896. After settling in Kansas City, he went into the grocery business, then began buying up real estate. He opened Fairyland Park in 1923. It would be in the family until its closing in 1977.

Fairyland Park fast became a popular destination. You could get there on the streetcar for a nickel. For just more than $1 you could see local and national performers.

The smell of popcorn, the rattling of the wooden roller coaster, the clanging of the carnival games, and the splashing from the giant Crystal Pool attracted young and old alike.

Accurso says she started working at the park when she was 12. She stayed on after high school, and as an adult when her brothers took over after heir father he retired.

She got to know many of the clients, who eyed her job with envy.

“I worked the concession selling popcorn and cotton candy and snow cones and worked some of the games,” she says.

Important to Kansas City culture

Fairyland Park was important to local musicians. Thousands would flock to the open air dance pavilion on sweltering summer evenings.

“During the summer the two main ballrooms in Kansas City, The Pla-Mor and the El Torreon, would shut down because didn’t have air conditioning,” says Chuck Haddix, Director of UMKC’s Marr Sound Archives, who wrote about Fairyland Park in his book on the history of Kansas City Jazz.

“For local bands, Fairyland Park provided them with work all summer long – Benny Moten and Jay McShann. Ironically they booked African-American bands when African-Americans were not allowed in the park.”

Racial divide

Maria Brancato Accurso says Fairyland wasn’t the only institution excluding black people.

Swope Park, a public park, excluded African-Americans from its swimming pool and for picnics they were segregated to Shelter #5 on what was called “Watermelon Hill.”

Accurso says her father was conforming to conventions of the time. She says he was a stubborn man and a shrewd businessman.

“He thought (integrating) was gonna hurt business a lot with the whites,” says Accurso. “He owned it privately, and to be told what you could do and what you can’t do when you own something yourself, that was tough for him.”

Margaret May, an African-American who grew up in Kansas City, felt the sting of that discrimination personally. When many of her friends would go to Fairyland on the one day of the year African-Americans were allowed in, her parents would not let her go. They told her if she couldn’t choose when to go, she wouldn’t go at all.

Now that Margaret May is older she says she sees why her parents made that decision.

“As an adult I can understand their reluctance and … when I became an adult, I didn’t let my kids go,” she says.

Civil rights

Civil rights protests came to Fairyland as protests at Kansas City lunch-countersand department stores escalated.

A group that was blocking the entrance to Fairyland was carted away in a paddy wagon, and the incident cast an unpopular spotlight on the segregated park. After that, Maria Brancato Accurso’s father, Mario Brancato, had no choice but to open the doors to black people.

With integration came white flight and declining attendance at the eastside park. Accurso waxes sentimental remembering her years at the park.

“They named it Fairyland and it was like Fairyland you know … that was the greatest thing a young kid could want,” she says.

The demise of Fairyland

In 1974, Worlds of Fun, Kansas City’s existing amusement park, opened. The state-of–the-art park created insurmountable competition for Fairyland.

Maintenance costs had become astronomical, and in 1977, a tumultuous storm bent the iconic Ferris wheel like a taco. Having survived five fires over the years, this time the family decided it was not worth the investment to rebuild, and the park closed.

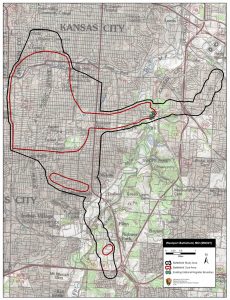

In the 1990s, U.S. route 71 bisected the park. Today, Satchel Paige School and a youth facility run by the Kansas City Police Department share the land.

This look at Kansas City’s east side is part of KCUR’s months-long examination of how geographic borders affect our daily lives in Kansas City. KCUR will go Beyond Our Borders and spark a community conversation through social outreach and innovative journalism.

We will share the history of these lines, how the borders affect the current Kansas City experience and what’s being done to bridge or dissolve them. Be a source for Beyond Our Borders: Share your perspective and experiences east of Troost with KC